An audio version of this article will be airing tomorrow night (Friday night, technically Saturday) at 12:00 a.m. Eastern on my radio show, The K-Pop Power Hour. Tune in at wesufm.org to listen live!

What is K-pop? It’s a deceptively complicated question. Those who aren’t devotees of the stuff might assume that it’s as simple as the name’s constituent parts: Korean pop music. But that’s not quite the case. When the phrase K-pop is used in Western settings, it’s typically synonymous with “idol” music, carefully preened boy bands, girl groups, and solo singers produced and groomed by management agencies. In other words, Ateez, IVE, and IU? Definitely K-pop. Lim Young-woong? Se So Neon? Popular Korean musical acts, but you’d be stretching it to call them K-pop.

But recently, a few different groups have come across my radar who, for one reason or another, have raised (largely online) debates among fans over whether they “count” as K-pop or not. These are the girl groups XG and Blackswan and the boy band WayV. This represented an interesting opportunity to explore what, in an ontological sense, it means to “be” a K-pop group, and the limits and challenges of hard categorization.

But these questions may also stem from a place of ethnic essentialism. To be blunt, a major reason the status of these groups as K-pop is questioned is that all of them are comprised of members of non-Korean backgrounds. Which in itself necessitates a discussion of the non-Korean presence in the genre.

Prologue: EXP Edition and the Issue of Non-Koreans in K-pop

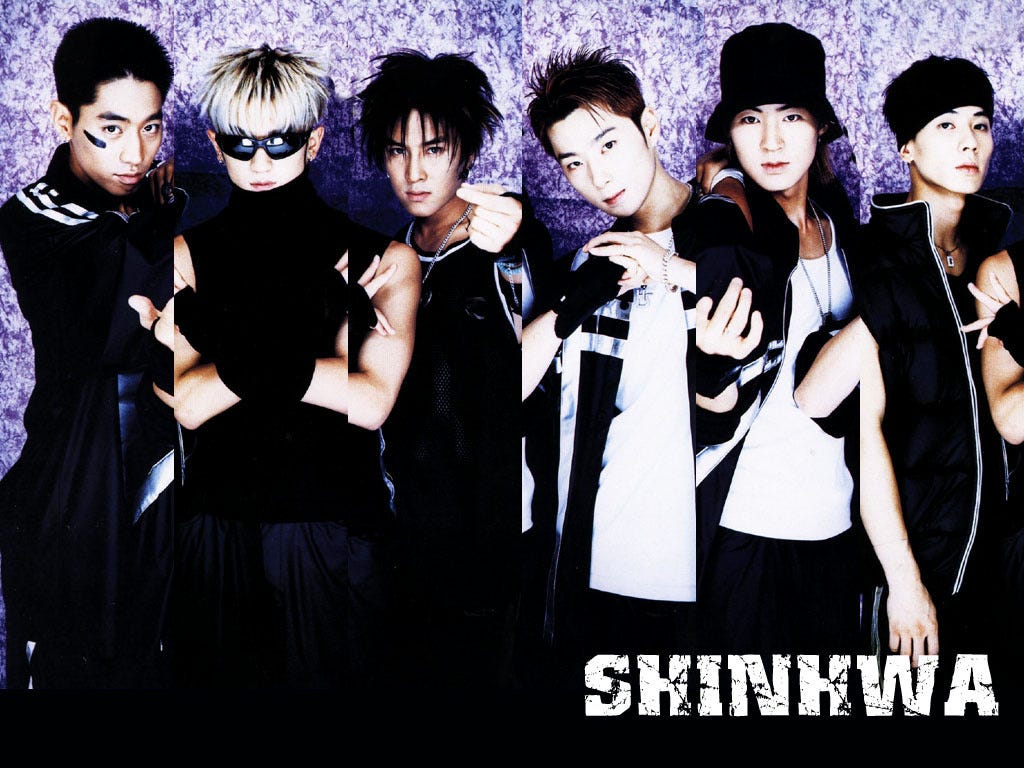

While the vast majority of K-pop singers are native-born South Koreans, there have been exceptions to this since the very beginning of modern K-pop. Among the so-called first generation of K-pop, from the mid-1990s through the early 2000s, this mostly meant those from the Korean diaspora: Korean Americans like Shinhwa’s Eric and Andy, or Zainichi (ethnic Koreans of Japanese nationality) like S.E.S’s Shoo.

The 2000s would see a rapid increase in the diversity of the mainstream K-pop world, with singers including Super Junior’s Han Geng (Chinese), 2PM’s Nichkhun (Thai American), and f(x)’s Amber (Taiwanese American), just to name a few. Soon it became common, even expected for K-pop groups to have a non-Korean member or two to boost their global appeal.

In the 2010s, this increased, with many popular groups having significant international membership. Of Twice’s nine members, four are non-Korean (three Japanese, one Taiwanese). Of Exo’s original 12 members, four were Chinese. In (G)I-DLE’s current five-member lineup, only two are Korean, with the other three being Thai, Chinese, and Taiwanese, respectively. However, these non-Korean idols are nearly always East or Southeast Asian. To be crude, the groups remained superficially cohesive.

One controversial exception to this came with EXP Edition. The boy band was assembled in 2015 as the MFA thesis project of Columbia University student Bora Kim, who set out to push the boundaries of K-pop by intentionally creating a K-pop style boy band made up of all non-Koreans.

The group’s original lineup consisted of Sime Kosta (Croatian), Frankie DaPonte (Portuguese American), Koki Tomlinson (mixed Japanese and German ancestry), Hunter Kohl (white American, I couldn’t find more specific details), David Wallace, and Tarion Anderson ( both African American).

After Kim was awarded her MFA, she wanted to continue the EXP Edition project, moving the group to Korea to promote themselves like a “real” K-pop act. Wallace and Anderson weren’t up for the move, whittling down the group’s lineup to what many online detractors would inaccurately call “a bunch of white guys.”

To say reactions from online K-pop fans were negative would be an understatement. I was active in K-pop fan spaces on YouTube, Twitter, Tumblr, and Reddit around the time of EXP Edition’s 2017 Korean debut, and I recall them being an all-around punching bag for fans of “real” K-pop. They were relentlessly mocked, and even reportedly received death threats.

Most puzzlingly, I frequently saw EXP Edition accused of cultural appropriation. This represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the concept. EXP Edition was not a case of Americans falsely laying claim to K-pop, they were the brainchild and pet project of a Korean woman seeking to push the boundaries of her native country’s pop culture.

Beyond that, to call EXP Edition cultural appropriators while accepting all of K-pop’s other non-Korean idols feels backhandedly racist. While intending to protect an Asian genre from white American encroachment, it ultimately conflates a diverse range of other Asian ethnicities and nationalities with Korean. It posits that a Thai American is somehow “close enough” to Korean in a way a Croatian isn’t. K-pop artists and labels have, for decades, employed non-Korean songwriters, producers, video directors, and more. The members of EXP Edition didn’t represent a fundamental change to the already international character of K-pop, it just threw off fans to see non-East Asian faces singing the songs.

However, I ultimately don’t consider EXP Edition a K-pop group. Not because of their ethnicity, but because of the circumstances of their formation; they didn’t emerge from the Korean recording industry and the “idol” system, they were a performance art project assembled to pay homage to and challenge that system.

Nonetheless, the controversy around them provides a solid jumping-off point for examining the issue of what, then, makes K-pop K-pop? Does it require a group to have Korean members? Sing in Korean? Be under a Korean label? All of those? None of those? Just vibes? It is these unresolved, nebulous questions that are at the core of debates over the status of these following groups as K-pop.

Case Study 1: XG

The girl group XG, an initialism for “eXtraordinary Girls,” made their debut in January of 2022, under the management of Xgalx, a subsidiary of the massive Japanese entertainment conglomerate Avex. All seven of the group’s members are of Japanese nationality and background, though two are of mixed ethnicity; rapper Harvey is of Japanese and white Australian descent, and vocalist Hinata is of Japanese and Korean descent.

With these facts alone, it would be easy to label XG as a J-pop group. Their members are Japanese. They’re under a Japanese label. However, it’s more complicated than that. All of XG’s music is in English, despite most of the members not being fluent in the language. The group has promoted itself much like a K-pop group, living in South Korea, performing on Korean music shows, and appearing on Korean television programs. Plus, there’s just the vibe. In terms of sound, aesthetics, and styling, XG are far closer to, say, Blackpink than they are to AKB48.

Because of all this, XG has accumulated, for lack of a better word, a K-pop fanbase. They’ve performed at multiple installments of KCON, a music festival whose lineup otherwise consists nearly entirely of K-pop acts. At KCON LA in August, XG even covered “I Am the Best,” a 2011 single from 2NE1 whose hard-hitting, hip-hop-inspired style XG clearly draws from. The crowd ate it up.

Because of all these elements, I’m hesitant to definitively declare XG K-pop or not. I could easily see them putting out music in Korean in the future, further integrating into the K-pop scene. But they’ve also never self-identified as such; they call themselves a “global girl group.” Combined with their all-English music, this could also mean they’ll go on to cast a wider net, setting their sights beyond just the Korean market. XG are a Japanese pop group who promote in South Korea and sing in English. Make of that what you will.

Case Study 2: Blackswan

If you’re not familiar with the thought experiment of the Ship of Theseus, let me offer a quick recap. In legend, the ship that belonged to the mythical Greek king Theseus was kept by the people of Athens for centuries as a memorial to their heroic founder. Over the years, the aged wood began to rot. Piece by piece, plank by plank, the ship’s parts were replaced. Eventually, not a single piece of original wood remained. Is it still the Ship of Theseus? If not, when did it stop being so?

The girl group Blackswan was founded, under their original name of Rania, in 2011. But none of its current members were in the group any earlier than 2020— three of the current four joined last year. In total, the group has had 24 members across its numerous incarnations.

For the first years of the group’s existence, Rania, as they were initially known, operated as a standard K-pop girl group: a mostly Korean lineup, with the occasional non-Korean-but-still-Asian member. Then, in 2015, they added rapper Alex to their ranks, who was billed as the first African American member of a K-pop girl group.

The next year, the group changed its name to BP Rania, with BP short for black pearl— an awkward reference to Alex’s race. Alex left BP Rania in 2017, after less than two years with the group. The group’s membership continued to shuffle. In 2020, they announced another rebrand, as Blackswan.

At this point, the group consisted of five members: Koreans Hyeme, Youngheun, and Judy, the Japanese Brazilian Leia, and the Senegalese-born Belgian Fatou. Hyeme left in 2020. Youngheun and Judy left in 2022, finally leaving Blackswan with no Korean members. New members NVee (American of mixed white and Black descent), Gabi (Brazilian of German descent), and Sriya (Indian) joined in 2022. That same year Leia went on an indefinite hiatus, leaving Blackswan with its current lineup, featuring not only no Korean members but no East Asian ones at all.

It’s the case of Blackswan that, at least for me, makes the idea that a K-pop group must have Korean members crumble. This brings us back to Theseus’s ship. At their formation, Rania was indisputably a K-pop group. Yet some might argue that Blackswan, in its current incarnation, isn’t. This posits, then, that at some point along the way, with a specific changing of the ship’s planks or reshuffling of members, the ship somehow stopped being that of Theseus, and Blackswan somehow stopped being K-pop.

The argument that Blackswan aren’t, but at some past point, were a K-pop group seems to place the essential “K-pop-ness” of the group into just two people: Judy and Youngheun, Blackswan’s two final Korean members. This seems like a heavy importance to place on just two members of a group that’s had over twenty. Plus, Blackswan is not one of those groups where the members are heavily involved in songwriting and production; the departure of Judy and Youngheun did not fundamentally alter Blackswan’s musical identity any more than the group’s many previous lineup shuffles did. To argue that the loss of Blackswan’s Korean members rendered the group “no longer K-pop” is to disregard all of the factors that shape a K-pop group, such as its language, industry, and management, in favor of a crude ethnic essentialism.

Blackswan are a product of the Korean idol management system. They are based in Korea and perform Korean-language pop music. They began as a group with a predominantly Korean lineup. They’re a K-pop group.

Case Study 3: WayV

WayV represents yet another twist in the saga of attempting to define ontological K-pop-ness. To understand WayV, I first have to back up and explain NCT. NCT is a project of K-pop mega label SM Entertainment that is both a boy band and a larger system. As a whole, NCT currently has 20 members, down from a peak of 23 (three departed this year, Lucas over scandals, Shotaro and Sungchan to become members of the new boy band Riize), with another seven on the way, preparing to officially debut in the upcoming spin-off tentatively named NCT Tokyo.

For the most part, the members of NCT are split into more manageable units. NCT 127 is based in Seoul and has an in-your-face sound rooted in industrial electronica and hip-hop. NCT Dream consists of the group’s youngest members and has a lighter pop style. WayV sits sonically somewhere between 127 and Dream, and primarily puts out music in Mandarin, aimed at the Chinese market.

So why wouldn’t WayV just be considered a C-pop or Mandopop group? None of the members of WayV are Korean. Kun, Winwin, and Xiaojun hail from mainland China, Ten is Thai of Chinese ancestry, Hendery is from Macau, Yangyang is from Taiwan, and former member Lucas is from Hong Kong.

But this is probably where I should mention one more subunit of NCT. Well, not quite a subunit. The label NCT U refers to a different grouping of members nearly every single time, shifting to whoever works best on a given song. A power ballad can feature just vocalists, a hip-hop track just rappers. Above all, NCT U songs are, undeniably, K-pop songs. They are in Korean, performed by predominantly Korean lineups, and, centrally, are the product of Korean idol management.

Because of this, every member of WayV has also performed on one NCT U track or another, singing in Korean alongside their Korean bandmates on songs that are undeniably K-pop. When operating in NCT U, the members of WayV are K-pop singers. Why, then, would they stop being K-pop singers when they’re in WayV?

What’s more, WayV has, in fact, operated just like a K-pop group in more respects than simply being under the NCT umbrella. Though WayV was formed to focus on the Chinese market, the worsening geopolitical relations between China and Korea in the last few years, not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic, made traveling to China for promotions difficult, and, at times, impossible for WayV. Thus, WayV promoted in Korea. They recorded their songs in Korean, performed on Korean music shows, and appeared on Korean variety shows, the works.

So, what’s the verdict on WayV? For me, it’s pretty clear. The members of WayV are based in Korea, managed by a Korean record label, and are in fact all members of the larger Korean-language boy band that is NCT. WayV is a K-pop group. They’re also a Mandopop group. Two things can be true at the same time!

Conclusion

K-pop itself is a poorly understood term, and often, disputes over what counts as K-pop come from the parties involved operating under different definitions of the word. Merriam-Webster’s dictionary offers the frustratingly vague “popular music originating in South Korea and encompassing a variety of styles.” By this definition, practically all music from South Korea is K-pop. But when most people talk about K-pop, when media outlets write about BTS or Blackpink, they mean idol music, the system in which major record labels audition and scout talent for glossy, high-production pop acts. This system operates in South Korea, and the music it produces is in Korean. However, the singers involved are not universally Korean and have not been since the genre’s modern inception. It is this unique management style and blend of influences that, to me, characterizes K-pop, far more than the simple nationality of its singers.

The discourse over whether K-pop can be sung by non-Koreans is, quite literally, superficial. As I mentioned, fans seem to have no qualms about the behind-the-scenes talent of the K-pop scene being non-Korean. “Move” by Taemin, for example, is a popular, acclaimed K-pop song. Its singer and lyrics are Korean. No one would dispute its status as K-pop. Yet three of its four songwriters are American. The choreographer who crafted the song’s iconic routine is Japanese.

The international character of K-pop, bringing together global talents in a uniquely Korean context, is what makes it so exciting in the first place. To reduce the genre’s identity to the nationality or ethnicity of those who perform (but often do not write) the songs is to miss the point.