A "Killer" Double Feature

Two of this fall's best films see iconic directors interrogate their own oeuvres.

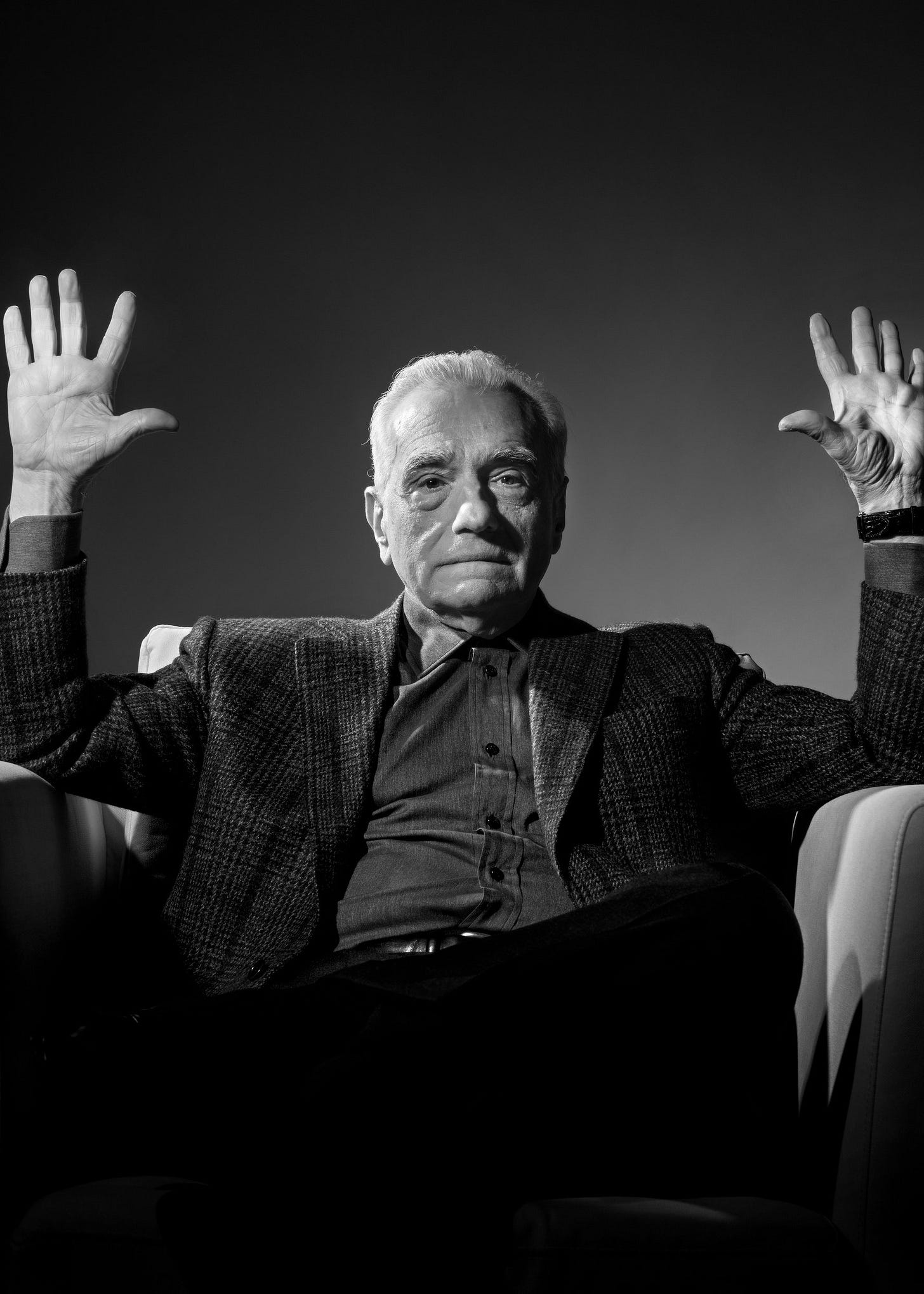

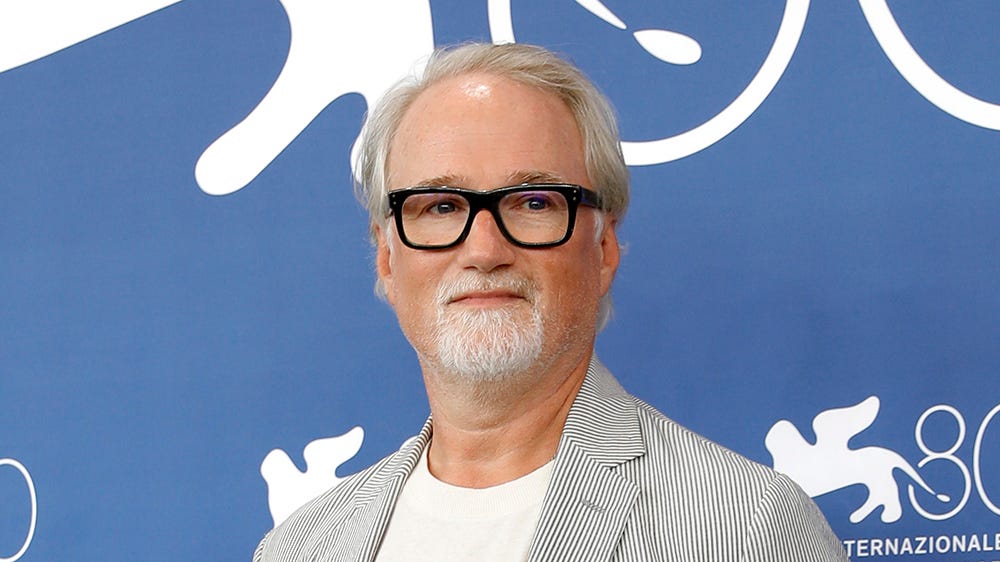

“Barbenheimer” was undeniably this year’s biggest double feature. But there’s another duo of great films that haven’t been widely discussed as a pair. These two movies were both released in late October, both distributed in theaters by major streaming services, made by great contemporary American auteur directors with plots that revolve around characters who, in the pursuit of fortune, commit horrific acts of murder, which both happen to have the word “killer” in their title: “Killers of the Flower Moon,” directed by Martin Scorsese and released by Apple TV+, and “The Killer,” directed by David Fincher and released by Netflix.

These two films are, to be clear, very different. Scorsese’s “Killers” is an epic, elegiac three-and-a-half-hour reckoning with a horrifying, overlooked chapter in American history: the early-20th century murders of members of the Osage Nation by white men seeking to usurp their wealth. Fincher’s “Killer” is a tight, tense thriller about a fictional hitman, adapted from the French comic by writer Matz and artist Luc Jacamon and clocking in at under two hours. But they share a surprising, fascinating creative ethos; both of these films see iconic directors directly confronting the style of films they’ve become known for, challenging both their audiences and their own legacies.

Scorsese’s filmography is more diverse in tone and subject matter than some might give him credit for. He makes far more than “mob movies,” though those are some of his best films. But across decades of work, a recurring theme of Scorsese’s is the depravity of the American male psyche, what we might, in the contemporary lexicon, term “toxic masculinity.” This is a theme he carries through to “Killers of the Flower Moon” in particular, its two leading men. But there’s also a clear break between them and other iconic Scorsese protagonists based on real-life wrongdoers.

Sure, characters like Henry Hill in “Goodfellas” and Jordan Belfort in “The Wolf of Wall Street” are scumbags. They do terrible things, destroy people’s lives, and ultimately face the consequences of their actions. But they also dress well, live glamorously, and are played with great charisma by handsome movie stars; it’s not impossible to see how someone might come away from these films wanting, on some level, to be like them.

By contrast, “Killers” leading man Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) is utterly pathetic and despicable from his actions down to his demeanor. DiCaprio, famously one of those handsome movie stars, is shrouded behind greasy hair, grey teeth, and rumpled, sweat-stained shirts. There’s no charm or cool to his performance, just a miserable, deeply rotten man. His uncle, William King Hale (Robert De Niro), the lead planner of the systemic murder of the Osage, doesn’t come off as a calculating mastermind but as a cruel twist on the affable old man persona De Niro has cultivated in more recent comedic work.

The filmmaker and critic François Truffaut argued that it is impossible to make a truly anti-war film, for depicting violence in the cinematic medium is inherently glamorizing. Scorsese seems to have taken up Truffaut’s argument as a challenge; the violence in “Killers of the Flower Moon” is among the least entertaining, exciting, or glamorized I’ve ever seen. Evil has never been less fun.

The film’s final scene is Scorsese’s most directly confrontational. We are taken away from the characters with whom we have just spent upwards of three hours, and instead, learn about how things ended through the presentation of a radio play before a packed theater. We see before our very eyes how this real-life tragedy was made into entertainment, forcing us to question the ethics of even the very film we have watched. Scorsese himself even appears as one of the presenters, narrating that when Ernest’s long-suffering Osage wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), died years later, her obituary did not mention the murders her husband committed against her family.

The closing image of “Killers of the Flower Moon” leaves us, emphatically, with the Osage, as we see jubilant footage of a traditional dance circle. Though we might initially think it’s from the 1920s era of the rest of the film, we soon notice the contemporary attire of the dancers and realize that we are seeing the Osage in the present day, still thriving a century after Burkhart, Hale, and their co-conspirators attempted to destroy them. Scorsese’s message couldn’t be clearer: it is with these people that our hearts should rest, not those who preyed on them.

Fincher is well-versed in depicting the meticulous machinations of monsters. But from John Doe’s elaborate murder tableaux in “Seven” to Amy Dunne’s airtight alibi in “Gone Girl,” sociopaths in Fincher movies are often entertainingly hypercompetent. They’ve figured out everything, outfoxing the heroes and the authorities, leaving their victims helpless to resist. In “The Killer,” this concept is undercut in the film’s very first sequence.

We begin with a lengthy voiceover in which the unnamed titular hitman (Michael Fassbender) explains his uber-precise modus operandi. Stick to the plan. Don’t improvise, he repeatedly intones. We see him prepare his work in excruciatingly precise detail. Yet for the very first kill of the film, a simple sniper operation, he misses his shot, killing a dominatrix instead of the intended target, her wealthy client. He swears and frantically disassembles his gear, rushing out of dodge before law enforcement arrives.

This irony is the dramatic foundation upon which “The Killer” is built. Moment-to-moment, the film operates as a traditional thriller. We viewers bite our nails as Fassbender sneaks into a location, wince at the brutal acts of violence he carries out, and puzzle alongside him as he untangles the conspiracy against him he must fight for his own survival. Yet, there’s a deep, dryly humorous undercurrent to the entire thing because, to put it bluntly, the titular killer is far from the precise, slick hitman we initially assume he is. Every plan he makes goes awry in one way or another. He decries improvisation, yet constantly does it. He espouses remaining detached and unemotional, yet is entirely driven by personal grudges and whims. He’s constantly listening to The Smiths, those iconic purveyors of archly emotional angst anthems. He wishes he was a cold-blooded assassin in the sort of Fincher project one might expect. Instead, he’s a bumbling try-hard in a new type of film for the director.

Some critics have gone as far as to suggest that “The Killer” is a reflection on Fincher’s own process, with its representations of a meticulous, frustrated professional paralleling the director’s famously precise, exacting shooting style. This interpretation has been rejected by Fincher himself, who dismissed it as “weak-minded.” But there is something clearly reflective about “The Killer,” if not for the director himself, then certainly on his oeuvre.

Like Scorsese, Fincher has built his career on films that highlight immoral behavior but do so with such style as to potentially cause people to become overly fond of these cinematic wrongdoers. Both “The Killer” and “Killers of the Flower Moon” represent fascinating turns for these iconic directors, creating excellent new films that fit into the themes and narratives of their earlier work, while simultaneously working to subvert them. It’s this new, reflective dimension that makes these films from directors decades into their careers feel as fresh and vital as ever.